China to Close 2,000 Factories for Energy Inefficiency

The Globe and Mail reports today that the Chinese central administration plans to close over 2,000 manufacturing plants, primarily producers of steel, paper, cement and aluminium. Story below:

Energy push shuts Chinese factories

Beijing — Globe and Mail

Update Published on Monday, Aug. 09, 2010 1:11PM EDT

China has ordered 2,087 steel and cement mills and other factories with poor energy efficiency to close as the country struggles to cut waste and improve its battered environment.

The “backward” facilities produce steel, coke, aluminum, paper and other materials throughout China![]() and must close by late September, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced Sunday.

and must close by late September, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced Sunday.

Authorities said last week that a five-year plan to improve energy efficiency suffered a setback this year as China’s economic rebound and a construction boom boosted demand for steel, cement and other energy-intensive products.

The plan calls for a 20 per cent reduction in China’s energy consumption per unit of economic output, or energy intensity, by the end of this year. The government said in March it had cut energy intensity 14.4 per cent by the end of 2009 but it said last week that energy intensity crept up 0.09 per cent in the first half of this year.

China overtook the United States![]() last year as the world’s biggest energy consumer, though with a larger population it still is well behind in consumption per person, according to the International Energy Agency.

last year as the world’s biggest energy consumer, though with a larger population it still is well behind in consumption per person, according to the International Energy Agency.

China’s surging energy demands have alarmed communist leaders, who worry about dependence on imported oil and gas from volatile regions such as the Gulf and pollution damage to scarce water supplies and forests in a densely populated country.

The country’s growing presence in international energy markets has prompted complaints that it is pushing up crude prices and making supply deals with international pariahs such as Iran and Sudan.

China is the world’s biggest steel producer and a major producer of other industrial materials as well. Its newest facilities are equipped with the latest technology but there are thousands of small, outdated paper mills and other businesses that local authorities are reluctant to close for the sake of jobs and tax revenue.

In the latest crackdown, the facilities would lose their certification to emit pollutants at the end of September, utilities would cut off power supplies and banks would be ordered to stop dealing with them, the ministry said.

Its list included 762 cement factories, 279 paper mills, 175 steel mills, 192 coking plants and an unspecified number of aluminum mills.

Provinces with the biggest numbers of affected facilities are Henan in central China and Shaanxi in the north, both traditional centers for heavy industry, with more than 200 each.

Beijing warned in March that China was lagging on efficiency due to its stimulus, which was based in part on pumping money into the economy through massive spending on building new highways and other public works. Banks also were ordered to lend more to support private sector construction.

That set back government efforts to shift the economy away from heavy manufacturing and toward more technology-based businesses and cleaner service industries.

The economy grew by 11.9 per cent in the first quarter over a year earlier and by 10.3 per cent in the second quarter. Stimulus spending and a flood of lending by state banks helped to boost growth from a low of 6.1 per cent in the first quarter of 2009.

Chinese industries use 20 to 100 per cent more energy per unit of output than their U.S., Japanese and other counterparts, according to the World Bank. Chinese officials say energy use is 3.4 times the world average.

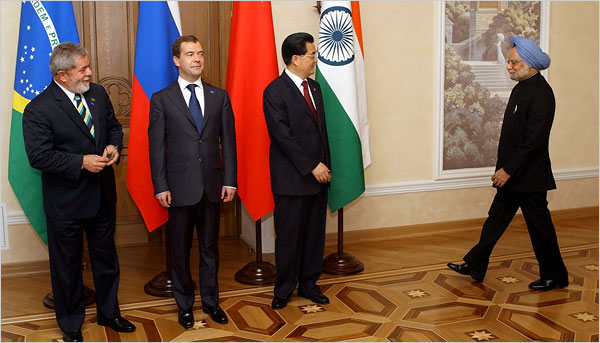

BRIC Group on Energy and Climate

On 16 June 2009, the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India and China (or BRIC) met in Yekaterinburg at the base of the Ural Mountains for their first official summit. Touted as the four leading non-Western economies, the BRIC group have assumed increasingly active roles in the world system over the past decade. Playing host to the summit – alongside a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – Russia has taken great steps to up its diplomatic profile as it balances its international obligations, economic renewal, energy wealth and historical super-power.

Top on the agenda were economic issues, such as national stimulus, fiscal imbalances and trade protectionism, encouraging continued cooperation by the BRIC countries through the G20 summit process. Among the key initiatives set out in the Joint Statement of the BRIC Countries’ Leaders was the reform of international financial institutions to better represent the current/future global economic order. Any reform should adhere to democratic and transparent decision-making, must be rules-based and enforce compliance, and provide a greater voice to emerging economies.

Of particular interest was their statement on energy issues. Three relevant paragraphs state;

7.The implementation of the concept of sustainable development, comprising, inter alia, the Rio Declaration, Agenda for the 21st Century and multilateral environmental agreements, should be a major vector in the change of paradigm of economic development.

8.We stand for strengthening coordination and cooperation among states in the energy field, including amongst energy producers and consumers and transit states, in an effort to decrease uncertainty and ensure stability and sustainability. We support diversification of energy resources and supply, including renewable energy, security of energy transit routes and creation of new energy investments and infrastructure.

9.We support international cooperation in the field of energy efficiency. We stand ready for a constructive dialogue on how to deal with climate change based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, given the need to combine measures to protect the climate with steps to fulfill our socio-economic development tasks.

While it is not surprising that, as the continent’s major producer, the Russian hosts would include a declaration on energy issues. However, what does jump out is the maturity of the language. Paragraph 8 is among the first summit documents to recognize the three key categories of energy states; producers, consumers and transit. Often, the energy conundrum is distilled to a dyadic relationship between oil-rich states (OPEC) and importing countries (OECD). The reality is that after extraction natural resources pass through many hands and cross many borders before reaching the end user.

Any formula for legitimate global energy governance must include all three off these country categories. However, we cannot ignore the obvious motivations of the host, and its frequent politicking of oil/gas supply to Europe. When Russia hosted its first G8 leaders’ summit in 2006, it chose energy security as the critical point of discussion. In similar fashion to the BRIC summit, the host reminded its guests of the vast Russian reserves for sale, treating the opportunity like a used-car salesman would, shamelessly flaunting its wares. Then, as in now, there was an opportunity to engage high-level debate on what regulation/oversight is needed in the energy sector and what sort of body should enforce compliance. Such a body is unlikely to ever materialize, especially if countries like Russia – willing to use energy as an arm of security policy – set the mandate of discussion.

Later this year, the UN-led global climate regime will engage the emerging economies and the developing world at Copenhagen. The BRIC statement is a good indication of where the negotiations currently stand on bringing China, India and others into the post-Kyoto framework. Before it can be resolved, many concessions will be required of all countries, but it appears debate remains deadlocked in an emissions blame game, where everyone loses.

After four ministerial meetings, an informal leaders meeting and now a full summit, the BRIC group has demonstrated itself to be a potent source of global political discussions. With Brazil and Russia as major regional energy producers, and China and India as the world’s growing consumers, it is likely that issues of energy governance will continue to feature in their discussions. Each are also members of the US-led Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate, set to meet again alongside July’s G8 summit in L’Aquila, Italy.

It will be interesting to watch how cooperation within this group comes into its own through the G8’s Heiligendamm Process, the G20 economic summit, the Copenhagen climate conference, and the 2010 BRIC summit in Brazil.

Locating “Energy Security”

The term “energy security” evokes a variety of sentiments. The commonly accepted definition relates to the fundamental economic principle of sufficient supply to meet demand within a geographic space, at an acceptable cost. When applied across states and great distances, between producers and consumers, this equation becomes quite complicated.

Energy security has become infused with classic perceptions of national sovereignty, borders and economic development. It has also come to connote a sense of entitlement on the part of industrialized economies, giving rise to an “us versus them” scenario. Using the word “security” polarizes the debate, putting net exporters on one side and net importers on the other, and creates a system of conflict that may not otherwise exist.

In practice, transnational corporations control the extraction, refining, transportation and delivery of energy, and largely drive the energy sector. The concentration of power in private hands has thus handcuffed policy makers in many ways.

Energy security is seen by some as a purely strategic objective, requiring the militarization of oil fields and shipping routes; others approach the term from a political-economic perspective as a statement on the inequality in the world economy, favouring the promulgation of affluence in industrialized economies.

The rise of new global powers – China and India in particular – has added a level of complexity in how energy security is perceived from the perspective of the dominant powers. As reported in the 2007 World Energy Outlook, these countries are experiencing staggering rates of economic growth and are demanding an increased share of world energy resources. As traditional resources become more scarce and alternatives are introduced, the prevailing energy status quo will be challenged by the rise of the emerging economies (or BRICSAM). Securing sufficient supply to meet demand in these growing economies as well as the established industrialized economies will force competition or collaboration for more expensive supplies.

The preferred yet challenging path is that of collaboration, and submission to greater regulation in the global energy sector. Experts and scholars warn of looming energy wars if transition cannot be made to a low-carbon society. The likelihood of effective and efficient implementation of new technologies to lessen reliance on remaining fossil feuls – much of which controlled by rogue regimes – within the next couple decades is minute.

And yet, institutionally, this competition is promoted by a competing system of allegiances; OPEC and IEA. Without transparent, multistakeholder and universal governance mechanisms in global energy – every step from extraction to end user – this system will continue. A broader conceptual understanding of “energy security” is needed to inform global policy-making; one that encompasses poverty and development, science and technology, law and order, labour and environment as much as it does business and profit, trade and borders.

Governing Asymmetric Energy Relations

Last week, the Academic Council of the United Nations System (ACUNS) held its Annual Meeting at the St. Augustine Campus of the University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago. Under the theme, “Small, Middle and Emerging Powers in the UN System”, I was able to present some of my recent work on global energy governance.

Disruptions in predictable supply and demand of energy resources have far reaching impacts for all countries. At ACUNS, I examined the dual constraints of horizontal and vertical pressures put on the global system through the global energy conundrum. Horizontal in that every state – from small, middle to major – demand adequate and reliable flows of energy resources. And vertical in that energy resource wealth forces a recalculation of power across states of all sizes. Small states like Trinidad to middle powers like Canada bank on their energy wealth for economic influence, Brazil as an emerging power has led on alternatives like ethanol, at the same time when the United States (although still the largest producer in the Hemisphere) is heavily reliant on imports from its smaller neighbours to sustain its energy demands.

Conspicuously absent in the international system are real mechanisms for global energy governance. The two institutions that exist at the inter-governmental level have constrained mandates focused on the interests of their selected member-states. In both organizations, energy security is strongly perceived through a nationalistic lens.

On the one hand there is OPEC, a group of major oil-producing nations that acts as a bloc to maintain pressure on the world price through collective supply quotas. On the other there is the International Energy Agency (IEA), within the OECD, which provides detailed statistics and policy advice to the world’s wealthiest and highest oil consuming nations, most of which depend on substantial imports from OPEC members.

Energy policy, nationally and internationally, is often interrupted by environmental policy, or even seen as a sub-set of climate change issues. Rather, energy should be the issue of policy primacy in all related discussions. Although more prominent in public discussions, environmental issues should be treated as symptoms, with energy policy being used to address the root causes of climate change.

Further analysis is needed to suggest whether market-based or policy-based approaches would be more influential in practical solutions. Under current economic conditions, governments are unlikely to be concerned by industrial emissions or inclined to fund massive infrastructure upgrades without incurring serious repercussions.

The world economy needs global energy governance to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy; mediate resource conflicts; enforce regulatory compliance; encourage clean economic development; secure critical infrastructure; support R&D; stabilize prices; and, advise on the best ways to do all of these things.

The G8 has demonstrated its inability to have vision in this area beyond the interests of its select membership. The NATO Forum on Energy Security focuses heavily on narrow strategic interests. The International Energy Forum remains a talk-shop for business leaders with little policy influence. Sadly, the common thread among each major initiative to address energy security has been protection of Northern lifestyles. Only the UN System has the necessary credibility and global reach to advance this aggressive agenda.

Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate

In this video, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outlines the MEF as a preparatory group for the Copenhagen climate conference.

World Economy Needs Energy Governance

While calendar years may only be arbitrary temporal assignments of lunar cycles, it brings great solace to see some years come to a close. Certainly, the year 2008 is one that no energy executive/ labourer/ analyst /watcher will chose to repeat any time soon.

There are just too many developments to mention, but most 2008 energy episodes centre on the extreme price peak of crude oil futures. While the NYMEX recorded one $100/barrel transaction on 2 January, it took a month before it settled above the unsettling price level. Speculation continued unabated, reaching the record-shattering price of $147/barrel on 11 July. If not improbable, the rise of oil prices was only surpassed in popular disbelief by its rapid and debilitating fall, closing the year at $35/barrel. However, 2008 will likely be remembered by most for the sudden crash of stock markets around the world, netting trillions in evaporated wealth.

From a global governance perspective, it was perhaps the food-fuel conflict that drew the greatest response. World governments and international institutions were called upon to intervene in the mounting crisis that punished the world’s most vulnerable populations by causing a rise in fundamental food products, as a result of industrialized countries adopting alternative fuel technologies. Looking back, the events/decisions that led to the conflict could be characterized as “ignorant well-intentioned entitlement”: Entitled as the rich nations chose these fuel sources to sustain/increase their already dangerously high rates of energy consumption; Well-intentioned as the move to sugar/corn-based ethanol was meant to increase alternative energy sources, in the spirit of reducing fossil fuel emissions; and, Ignorant as the policies which set the process in motion (at least in the U.S. congressional hearings) failed to consider the price effects on food in the developing world, assuming that there would be added motivation to increase production capacity.

In the end, it wasn’t until the price of oil crashed that food prices were able to normalize. This occurred for two reasons; a lower oil price reduced incentives toward ethanol production, and the petroleum-intensive soft costs of food (fertilizers, tractor fuel, transportation, etc.) all became immediately cheaper. While pressure was focused on governments to provide answers – with the issue even made it to the G8 agenda – the bulk of responsibility lies with corporations and lobby-groups (with little accountability). Granted that institutions of state or supra-state authority have the obligation to foresee crises and adjust accordingly, it is often those self-interested actors that find ways to abuse under-regulated systems to their advantage – a hard lesson-learned from the reverberating financial crisis.

One interpretation of the moral of this story could be that universal, diverse, multilevel, legitimate, and effective institutions of energy governance are needed to curtail preventable conflicts. The 2008 clash of food and fuel demonstrated that when policy-making in (seemingly distant) resource sectors does not consider the wider social and economic effects among different constituencies, devastating consequences can result. Certainly there is a political appetite for regulatory bodies with innovative solutions – note that IRENA came about within a year – but such an initiative requires a champion.

So far, a credible champion has yet to emerge. Governments warn of the limits to economic growth; corporations fear regulation; and think tanks say it deserves comprehensive analysis. The most advanced thinkers on these concepts are perhaps the peak oil theorists. As profiled earlier, initiatives such as the Oil Depletion Protocol and organizations such as Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO) offer creative responses to now reinforced notions of resource scarcity.

However, debate on their ideas too often get caught up in a debate on the science of peak oil at the global level. Its advocates are given unfortunate labels of “Doomsdayists” or “Militant Enivornmentalists”. The general hesitation to the peak oil thesis should not result in a rejection of the emanating policy proposals. Basic rules of game theory apply – the safest bet is to accept the premise and plan accordingly, for the human, environmental and actual costs of doing nothing could be insurmountable.

The world economy needs global energy governance to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy; mediate resource conflicts; enforce regulatory compliance; encourage economic development; secure critical infrastructure; support R&D; stabilize prices; and, advise on the best ways to do all of these things. In the same way that the peak of the oil price spike preceded (and perhaps precipitated) the stock market collapse of September, so too should the international response to the energy dilemma precede long-term economic corrections. Energy is the lifeblood of all economic activity – fixing the global energy imbalance, supporting needs-based solutions and building a green industrial sector may offer the world economy the shot in the arm it so badly needs.

IRENA: Governing (Renewable) Energy

Last week, a new and exciting step towards global energy governance took shape with official establishment of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). An initiative driven by the governments of Germany, Denmark and Spain, IRENA is expected to become the leading international institution exclusively responsible for the promotion of renewable energy adoption, research and technology sharing among a diverse group of industrialized and developing countries.

Over the course of last nine months, a series of international meetings and workshops were convened to chart out IRENA’s ambitious mandate leading into the 26 January 2009 founding conference in Bonn, Germany. Over 150 national or institutional representatives participated in the preparatory sessions towards the production of the Statute of IRENA, which will act as the foundational document of the burgeoning international energy body.

Over the course of last nine months, a series of international meetings and workshops were convened to chart out IRENA’s ambitious mandate leading into the 26 January 2009 founding conference in Bonn, Germany. Over 150 national or institutional representatives participated in the preparatory sessions towards the production of the Statute of IRENA, which will act as the foundational document of the burgeoning international energy body.

The Statute outlines IRENA’s goal to become the main driving force in promoting a rapid transition towards the widespread and sustainable use of renewable energy on a global scale. In support of these efforts, IRENA will;

… provide practical advice and support for both industrialised and developing countries, help them improve their regulatory frameworks and build capacity. The agency will facilitate access to all relevant information including reliable data on the potential of renewable energy, best practices, effective financial mechanisms and state-of-the-art technological expertise. (Source: About IRENA)

IRENA has emerged amid frustrations with decision-making in the International Energy Agency (IEA), its disinterest in the promotion of renewable energies, and its limited regulatory reach. While the IEA is an influential energy body – sometimes seen as the oil consuming countries’ counter-balance to OPEC – some members (and non-members) have expressed discontent with its lack of concern for climate issues and the introduction of alternatives.

With an initial budget of €25m, IRENA will spend the next year choosing a headquarters and secretariat as well as pushing national ratifications before launching full operations in 2010. Its supporters are quite optimistic on the agency’s future relevance and influence. Hermann Scheer is reported to have said, “Irena is the single-most important step for a speedy global introduction of renewable energies. It will give an enormous push to the use of renewables around the globe.” As president of the World Council for Renewable Energy, Scheer has worked to turn the rapid groundswell of attention on climate issues into support for a legal, standards-setting body.

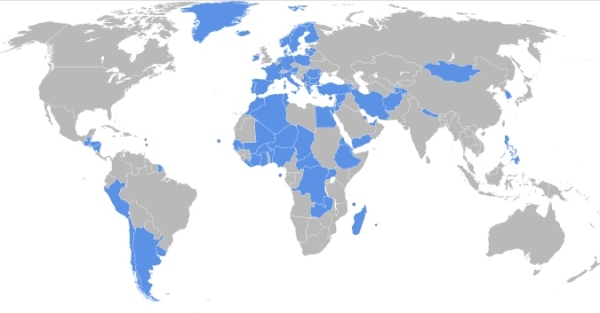

Initial support for IRENA is quite impressive. However, conspicuously absent from the 75 original signatories are G8 countries Canada, Japan, Russia, United Kingdom, and United States; and global South leaders such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa. Notably, membership of this ‘coalition of the green’ (so far) boasts strong connections among European and African states (see map); and, most shockingly, a healthy participation of OPEC, with Algeria, Iran, Nigeria and United Arab Emirates signing onto the Statute. Supporters of the process have included smaller states such as Iceland (pop. 300,000), Mali (GDP $530/cap.), Montenegro (est. 2006), and São Tomé and Principe (950km2).

- Geographic distribution of IRENA membership.

What IRENA has done better than other organization is to reach across the industrialized–developing country divide (aka North-South), constructing early legitimacy from a diverse constituency. Other initiatives toward global energy governance have not escaped the ‘club’ mentality, constraining themselves with like-mindedness and self-interest. First and foremost, the IEA (as an agency of the exclusive OECD) is comprised of a wealthy, industrialized, energy import-dependent membership, and as such not representative of the global energy system. It functions solely in support of its members, supplying detailed information and policy analysis on energy market trends – the IEA is not an advocacy or governing body, thereby sustaining a status-quo stance on some of the world’s most pressing energy challenges.

A fairly recent initiative, the G8-oriented Major Economies Meeting on Energy Security and Climate Change (or MEM-16), has attempted to offer palatable climate change policies for resisters of the Kyoto Protocol. Driven mainly by conservative governments who fear environmental protections as threats to economic output (including IEA members United States, Australia, Japan and Canada), the MEM-16 has so far offered only weak prescriptive measures and little in the way of substantive climate policy. Also among the institutions addressing energy is the NATO security alliance, working to secure the international petroleum transportation infrastructure. A special division of NATO is slowly implementing surveillance and protection of critical shipping routes and pipelines.

IRENA is different as it appreciates that while energy is the lifeblood of all economic activity; a) dependence on exhaustable resources and destructive technologies does not suit long-term economic interests, and b) we’re all in it together. The institution benefits from forward thinking – next-generation environmentalism – that is able to adopt favourable policies that can benefit firms and the market at the same time as protecting the environment. It has also placed developing countries at the core, understanding that there are great opportunities for renewable energy to provide sustainable development. However, some structural and functional challenges lie ahead. On the former, IRENA lacks the participation of the major emerging economies (BRICSAM and others) who are largely responsible for recent increase in fossil feul consumption, and arguably the countries most in need of alternative energies. On the latter, any international institution is only as good as the compliance of its membership to match national policy with international agreements. Thus far, the record of compliance on climate policies is dismal.

Meanwhile, the biggest stumbling block for IRENA’s success remains the absence of a U.S. signatory. The American Council on Renewable Energy (ACORE) actively participated in the preparatory meetings and has placed pressure on Washington to join IRENA. There are early signs that the new administration may be listening. U.S. President Barack Obama’s environmental memorandum (also of 26 January, see Climate CHANGE: Obama-style) provides much anticipation that membership may be possible in the coming months. His official request of the newly minted transport secretary to enforce the EPA’s energy efficiency standards and to lift federal restrictions on alternative energy sourcing are both positive indications of an administration willing to engage in mature environmental policy. As the U.S. prepares its climate diplomacy towards the December 2008 UNFCCC in Copenhagen (likely directed by new energy secretary Steven Chu), it will be interesting to see how other leaders/governments respond to the initiatives of the magnetic president.

The moral leadership demonstrated by IRENA’s drivers have brought the institution to fruition. From here on, it will be its capability to deliver action that will seal IRENA’s fate as either an ineffectual, idealistic body or a lodestar for global energy governance. What IRENA has proven so far is that there is widespread interest in casting off the ‘business-as-usual’ approach to international energy challenges, and to introduce innovative mechanisms for collaborative policy development, technology upgrading and knowledge sharing. Expectations are very high – it’s now up to IRENA to deliver.

Climate CHANGE: Obama-style

On 26 January 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama sent a clear indication that he would no longer accept status quo policy on the environment. By Presidential Memoranda, he erased the Bush administration’s historic refusal to allow California and more than a dozen other states to impose strict controls on exhaust emissions. He also ordered the transport department to raise the average fuel efficiency of the US automobile fleet to 35 miles per gallon by 2020, beginning with 2011 models. Below is the full-text of the memorandum.

In the year that the world works towards new environmental standards and emissions-reductions, this early indication that the Obama administration takes its climate obligations seriously is a good sign for us all.

——————-

| MEMORANDUM FOR | THE SECRETARY OF TRANSPORTATION THE ADMINISTRATOR OF THE NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION |

SUBJECT: The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007

In 2007, the Congress passed the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA). This law mandates that, as part of the Nation’s efforts to achieve energy independence, the Secretary of Transportation prescribe annual fuel economy increases for automobiles, beginning with model year 2011, resulting in a combined fuel economy fleet average of at least 35 miles per gallon by model year 2020. On May 2, 2008, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking entitled Average Fuel Economy Standards, Passenger Cars and Light Trucks; Model Years 2011-2015, 73 Fed. Reg. 24352. In the notice and comment period, the NHTSA received numerous comments, some of them contending that certain aspects of the proposed rule, including appendices providing for preemption of State laws, were inconsistent with provisions of EISA and the Supreme Court’s decision in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, 549 U.S. 497 (2007).

THE WHITE HOUSE, January 26, 2009

Required Reading: World Energy Outlook 2008

The International Energy Agency (IEA) released today its annual World Energy Outlook 2008 – widely respected as the publication of record on global energy statistics and analysis.

The WEO-2008 directly tackles the question of peak oil and the security of supplies, as well as climate change policies amid financial crisis. It provides detailed analysis of remaining stocks, anticipated discoveries, and progress on C02 reductions. This research has been designed to filter into early negotiations towards the December 2009 Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, of the UNFCCC. This will be the first agreement where both industrialized and developing countries will negotiate on the same terms – China and India will (hopefully) be brought into the post-Kyoto emissions system, alongside the United States and Japan. Previous WEOs may serve as reference in these deliberations, as the 2006 took an exclusive look at the BRIC economies and their expected energy demands.

At the London launch of the report, IEA Executive Director Nobuo Tanaka stressed, that “We cannot let the financial and economic crisis delay the policy action that is urgently needed to ensure secure energy supplies and to curtail rising emissions of greenhouse gases. We must usher in a global energy revolution by improving energy efficiency and increasing the deployment of low-carbon energy.” The annual launch of the WEO creates a buzz around international energy issues, demonstrating the potential of the IEA to act as a global regulatory body on energy. Every November, we are teased us ever so slightly as to the prospects of true global energy governance, but let down by the near ‘think-tank’ nature of the IEA and its limited enforcement capacity.

Below is a promotional blurb for the WEO-2008 – highly recommended reading:

World Energy Outlook 2008

Are world oil and gas supplies under threat? How could a new international accord on stabilising greenhouse-gas emissions affect global energy markets? World Energy Outlook 2008 answers these and other burning questions.

WEO-2008 draws on the experience of another turbulent year in energy markets to provide new energy projections to 2030, region by region and fuel by fuel. It incorporates the latest data and policies.

WEO-2008 focuses on two pressing issues facing the energy sector today:

– Prospects for oil and gas production: How much oil and gas exists and how much can be produced? Will investment be adequate? Through field-by-field analysis of production trends at 800 of the world�s largest oilfields, an assessment of the potential for finding and developing new reserves and a bottom-up analysis of upstream costs and investment, WEO-2008 takes a hard look at future global oil and gas supply.

– Post-2012 climate scenarios: What emissions limits might emerge from current international negotiations on climate change? What role could cap-and-trade and sectoral approaches play in moving to a low-carbon energy future? Two different scenarios are assessed, one in which the atmospheric concentration of emissions is stabilised at 550 parts per million (ppm) in CO2 equivalent terms and the second at the still more ambitious level of 450ppm. The implications for energy demand, prices, investment, air pollution and energy security are fully spelt out. This ground-breaking analysis will enable policy makers to distill the key choices as they strive to agree in Copenhagen in 2009 on a post-Kyoto climate framework.

With extensive data, detailed projections and in-depth analysis, WEO-2008 provides invaluable insights into the prospects for the global energy market and what they mean for climate change.

Lowering Expectations: Major Economies Meeting

On the final day of this year’s G8 Summit in Hokkaido Toyako, Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda welcomed an additional eight leaders for a working lunch, under the auspices of the Major Economies Meeting (MEM) on Energy Security and Climate Change. This included the countries engaged in the Heiligendamm Process, China, India, Brazil, South Africa and Mexico, plus Australia, Indonesia and South Korea. The outputs from this meeting, however, are likely to be soon forgotten or at best ignored.

Bad Policy

The showcasing of Fukuda’s much hyped “Cool Earth” climate policy ensured that energy security – although in the meeting’s title – would not get time on this year’s agenda. The G8 has dealt with energy only in narrow, self-interested ways. One of its founding motivations was to collectively respond to the Oil Crisis of the mid-1970s and again in the early-1980s with the fall of the Shah of Iran in the interests of stabilizing their national economies. In the modern context, it has been Russia and Canada that have put energy on the agenda, however, both have done so to secure new oil contracts among the rich club. This dynamic played out once more at MEM, as the urgency of energy policy was crowded out by the popularity of climate policy.

Cool Earth – also known as the “50/50” strategy – advances that the G8 should cut emissions by 50% by 2050. However, as frequently identified, this proposal is severely flawed as it sets no start-date, no interim targets, no reporting mechanism, and no penalties for noncompliance. With a target date so far in the future, most of the G8 leaders are not likely to be alive in 2050 and certainly decades out of office. This initiative has proven that leader-driven climate policy is much more about image than substance. The policy implications of Cool Earth are few and far between, leaving most of the responsibility with the private sector to develop and implement new technologies while placing the much of the onus of reductions and energy efficiency on the MEM developing countries.

Growing Divisions

While many G8-watchers have made a persuasive argument for climate change as a functional case for G8 membership reform, the MEM certainly does not fill this role. While it brings a number of leaders from important countries into the G8 process, it does not provide a suitable forum to actively engage emerging powers in a two-way dialogue. At Toyako, the MEM took place as a “working lunch”, where prime minister Fukuda held court, taking up most of the session with an overly formal speech on Cool Earth. Any actual dialogue in the room was not going to change the wording of the declaration as all discussions took place pre-summit between officials. Even so, Fukuda failed to bring the full compliment of the MEM on-board.

Divisions between the G8 and its Heiligendamm Process partners – now calling themselves the “G5” – had been present before the summit, but at Toyako they got pushed into the public sphere. The G5 leaders met separately in Sapporo a day before the MEM to discuss issues of mutual interest and delivered a joint G5 Political Declaration and press conference, responding to the G8’s declarations on the world economy, climate change and food security. When it came to climate, the G5 were particularly pointed, shifting the onus of emissions reductions squarely on the G8, claiming that they are the states most responsible for today’s poor climate conditions. Instead of Japan’s 50/50 strategy, the G5 called for 80-95% CO2 reductions below 1990 levels by 2050 with mid-term targets of 25-40% reductions by 2020.

These short paragraphs on climate change advanced a much more progressive strategy to combatting climate change, while also setting appropriate measures for developing countries. Paragraph 18 of the declaration reads;

We, on our part, are committed to undertaking nationally appropriate mitigation and adaptation actions which also support sustainable development. We would increase the depth and range of these actions supported and enabled by financing, technology and capacity-building with a view to achieving a deviation from business-as-usual.

While paragraph 21 welcomed the proposals of China (for an ODA-type financing structure for climate initiatives, 0.5% of GDP) and of Mexico (for the establishment of a World Climate Change Fund). The G5 showed a maturity in the way it addressed climate change and accordingly none of the G5 leaders supported Japan’s MEM declaration.

Poor Leadership

Although often considered a “steering committee” for the world, when it comes to climate change, the G8 faces great opposition. Looking ahead to the UNFCCC’s 2009 meeting in Copenhagen where a post-Kyoto agenda to engage developing countries will be discussed, the G8 will likely be urged by the vast majority of states to share the bulk of emissions reductions. Is this unreasonable? No, quite the opposite. Will this be accomplished? Again, no, the G8 perceive mandated emissions reductions as a threat to economic sustainability.

Following the G5’s ground-breaking meeting in Sapporo, with their declared “consolidation of bilateral interests”, it is likely that in upcoming climate change discussions (Poznan 2008; Copenhagen 2009) a new form of South-South cooperation may develop. G5 leadership among the G77 bloc of developing countries is not unlikely, having roots in the IBSA Forum, G20-Trade, and the BRICs foreign ministers meetings. The climate agenda outlined in their Sapporo declaration will likely gain traction among the G77; a group that will help dictate the terms of a post-Kyoto framework.

The MEM will soon be a distant memory, where the impractical and inadequate strategies advanced by out-going leaders will be eclipsed by new priorities of new leaders. However, what the MEM has done is lowered expectations of action on climate by the world’s wealthiest states, stalled any serious activity towards addressing the world’s pressing climate crisis, and has solidified political support among the leading developing countries.